what would be an abiotic factor that may be important to the survival of white tail deer

Overview

A healthy and sustainable population of moose is important to Ontario.

These are some of the factors that influence moose in Ontario.

Hunting

In about parts of the province, hunting has an important effect on the population of moose.

Ontario has more than moose hunters than moose, at about:

- 91,000 provincially licensed moose hunters

- 78,000 moose in huntable areas (another thirteen,200 moose live in areas that aren't hunted)

Harvest management system

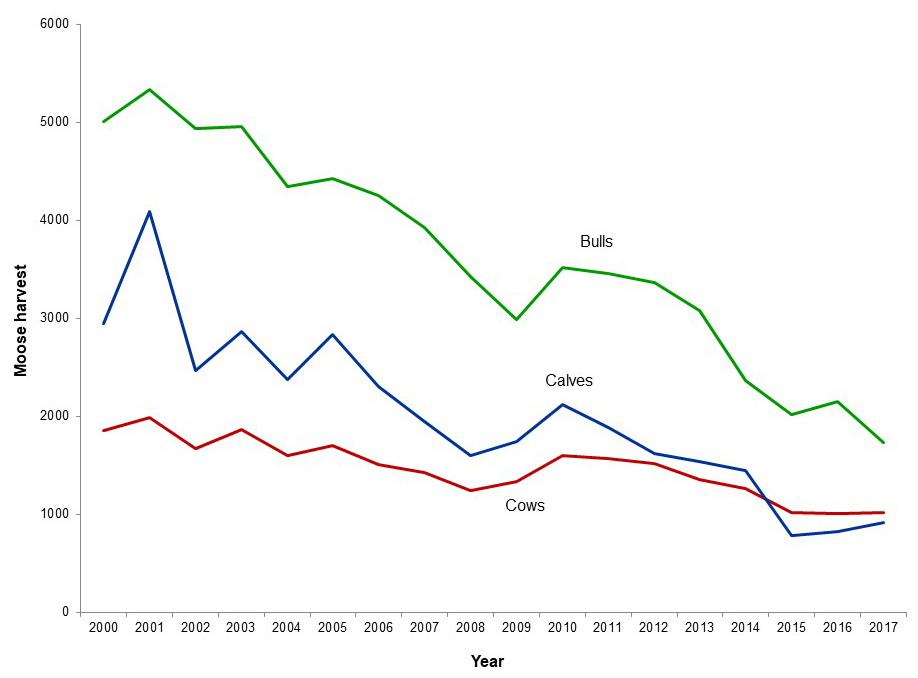

Ontario introduced the selective harvest organisation in 1983 to manage the moose harvest. Harvesting opportunities focus mainly on calves then on bulls, while cows are generally more protected for reproduction.

Moose harvest is also managed by:

- adjusting season timing and length

- expanse (due east.yard., Ontario's Wildlife Direction Units)

- regulating the type of firearms used

- allocating hunting opportunities

- delivering communication and education strategies

These measures are used to influence harvest levels in response to population trends and the number of bulls, cows and calves observed during aerial surveys. The proper limerick of the moose population affects overall survival and reproductive rates, and promotes moose population health.

The primal elements in applying the system are:

- developing sustainable harvest plans, which includes:

- considering population status relative to objectives

- setting biologically appropriate levels and proportions of bull, cow and calf harvest

- allocating tags to resident hunters and tourism outfitters

Read the Moose Harvest Management Guidelines

Emerging challenges

The selective harvest system has been successful, but new challenges have emerged and our understanding has changed.

Ontario'due south moose population grew from more than than lxxx,000 moose in the early 1980s to nigh 115,000 in the early 2000s. Only over the past decade, the population peaked and has since declined to an estimated 91,200 moose. The demand for moose hunting remains high.

Factors such as climatic change and parasites may exist putting more than stress on moose. In addition, contempo science suggests we need to reconsider how hunter harvest influences calf recruitment into the adult population.

Moose hunting trends in Ontario

Moose hunting has changed a great bargain since the early 1980s, when the selective harvest system was introduced. Hunting success rates for moose are higher today. Every bit a result, fewer adult validation tags can be issued today to attain the same level of moose harvest.

| Early 1980s | Today | |

|---|---|---|

| Moose population | eighty,000 | 91,200 (115,000 peak) |

| Hunters | 100,000 | 91,000 |

| Flavour length | 2-4 weeks | 2-iii months |

| Road access | Less road access in many WMUsouth | Increased road access |

| All-terrain vehicles | Limited use | Very common use |

| Wireless advice | Limited use | Very mutual apply |

| Political party hunting | No party hunting (no party harvest) | Party hunting |

| Success charge per unit | xx-thirty% gun; five-10% bow | 40-50% gun; 20-xxx% bow |

| Calf harvest | Very express | Substantial in many WMUs |

| Tags | Est. 47,000 adult validation tags (1984) | 10,757 adult validation tags for resident hunters (2018) |

In recent years, Ontario has seen a subtract in the provincial moose population and a corresponding subtract in available adult validation tags and moose harvest.

What we're doing

Moose populations may do good from changes to harvest direction in some areas.

Over the last decade, Ontario's moose population, while salubrious overall:

- has declined in some parts of the north

- has more often than not fared ameliorate in the southern part of the range

Tag reductions, and recent changes to hunting regulations, have been used to address concerns about moose populations in Ontario.

These concerns center on:

- the low and, in some cases, declining recruitment of calves into the breeding population

- the timing of the oestrus, or convenance period for moose, relative to the timing of hunting seasons

In southern Ontario, where hunting seasons are very limited and moose have fared better, modest increases in hunting opportunities may be considered in coming years.

Aboriginal and treaty rights

Ancient and treaty rights are of import considerations for moose management in Ontario.

Moose concord cultural significance for many Ancient peoples and continue to exist an of import traditional food source too. Many Aboriginal communities in Ontario hold Aboriginal and treaty rights to harvest moose for nutrient, social and ceremonial purposes. These harvesting rights mostly utilize within an Aboriginal community's specific treaty expanse or recognized traditional harvesting area.

Aboriginal and treaty rights are recognized in department 35 of Canada's Constitution Act, 1982. The courts accept clarified that, afterwards conservation needs are met, existing Aboriginal and treaty harvesting rights take priority in resource allocation and management.

The Ministry of Northern Development, Mines, Natural Resources and Forestry is working with Aboriginal groups and communities to proceeds a meliorate agreement of Aboriginal moose harvest, and ways we can piece of work together to accomplish common interests with respect to moose.

Habitat

Moose demand habitat that provides them with sufficient food and cover. They demand comprehend from predators and shelter from farthermost summer and winter weather. Moose motility between dissimilar types of habitat throughout the seasons to best come across these needs.

Moose numbers are often highest in parts of the forest disturbed by fire or forestry. Fire and forestry promote the growth of immature copse and shrubs, which provide nutritional food for moose.

Moose also crave more mature vegetation. It provides the shelter that moose need in summertime and winter.

Moose also need mineral licks, calving sites and aquatic feeding areas. These localized habitat features are very important for moose.

Moose numbers volition decline if one or more than key habitat components is lacking. Ideal moose habitat for browsing is forests anile most 5-30 years, and includes a mixture of young and mature forest.

Habitat management

Moose habitat is mainly managed through woods management on Crown land in Ontario.

The aims of wood management planning include:

- ensuring the overall quantity and quality of moose habitat reflects the range of natural variation in Ontario

- protecting the specific habitat features that benefit moose

Wood managers follow guides that give direction on creating and maintaining moose habitat:

- Forest Direction Guide for Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Landscapes

- Woods Management Guide for Boreal Landscapes

- Forest Management Guide for Conserving Biodiversity at the Stand and Site Scales, which aims to conserve forest biodiversity so Ontario's forests remain good for you and sustainable and protects important areas of moose habitat at the local scale, including winter cover, summertime cover and aquatic feeding areas

- Ontario's Cervid Ecological Framework, which provides mural-level habitat direction guidance for the province's cervid species (caribou, elk, moose and white-tailed deer), to exist considered when developing wood direction plans

Under this arroyo:

- forestry seeks to preserve the natural variation in young, middle-anile, old, hardwood, conifer, and mixed-wood forest types

- patches of disturbance produced through wood harvest and other human action are planned to emulate patches that are created by natural disturbances such as wildfire

This is done to ensure suitable habitat is bachelor for a range of species, including moose, across the broader mural.

What we're doing

In full general, habitat is not likely a limiting factor for moose in Ontario at the population levels at which they have existed historically. Even so, information technology tin affect the success and health of moose populations at smaller scales across the province. Ontario'due south approach to moose habitat management:

- recognizes the large scale pressures that influence wildlife, such as climatic change

- allows for an ecosystem approach to managing interacting species

- ensures that the needs of individual species, including moose, are met locally

Parasites and disease

While no known diseases have a major impact on moose abundance in Ontario, several parasites tin can contribute to declining moose numbers. Of these, brain worm and winter tick are the main concerns. Other parasites, such as liver fluke, also occur in Ontario, but are not known to affect moose numbers.

Brain worm

Brain worm is a roundworm commonly found in the encephalon of white-tailed deer. Information technology is common throughout eastern North America. Animals such as deer and moose get infected when they accidentally eat snails or slugs infected with brain worm larvae while feeding on vegetation.

Deer are unaffected past encephalon worm infections, simply in moose, these infections are usually fatal. Declines in moose populations mayhap related to brain worm accept been reported in northwestern Ontario, southeastern Manitoba, northwestern Minnesota, Northward Dakota, Michigan and Nova Scotia.

Signs of brain worm infections in moose vary but can include:

- toe-dragging or stumbling, disoriented behaviour, walking in circles

- farthermost weakness

- loss of fear of humans

- weight loss

- remaining in a pocket-size area for an extended menstruum of time

- inability to stand up

All ages of moose can be infected, but younger animals are generally affected more. In adults, encephalon worm is more than common in females than males.

Winter ticks

Winter ticks are a concern to moose in several parts of their range within eastern Northward America. Moose, along with elk and white-tailed deer are the primary hosts of winter ticks. In Ontario, the highest number of ticks found on a moose was 83,000, but the average is closer to 3,800.

Winter ticks touch on the moose population because they:

- feed on moose during the wintertime (heavily infested moose must replenish a significant amount of blood)

- cause moderate to severe hair loss during the wintertime and early spring

These effects can kill moose, peculiarly during March to April, as energy supplies dwindle at the end of winter and the potential for hypothermia rises in leap.

Liver fluke

Liver flukes are a big flatworm whose chief host is white-tailed deer, although moose tin also exist infected. In Ontario, liver flukes are generally institute effectually the upper Bang-up Lakes. They are limited to areas with certain types of snails that human action as intermediate hosts.

Liver flukes are transmitted when moose accidentally consume freshwater snails forth with vegetation. Liver flukes rarely infect young moose and are well-nigh mutual in centre-aged animals.

While no direct testify shows that liver flukes kill moose, some biologists believe that highly infested moose may be more than susceptible to other causes of death.

Other parasites and affliction

Other parasites and diseases that may infect moose are not known to cause declines in moose populations. These include skin tumours or warts, and hydatid cysts and moose measles (both of which are larval tapeworms). Peel tumours or warts are caused by a skin virus that does not affect humans or the edibility of moose meat. Hydatid cysts, the larval stage of tapeworms, are ordinarily institute in wolves. The tapeworm eggs (deposited through wolf carrion) are accidentally ingested by moose along with vegetation. These tapeworms have no directly effect on moose. Moose are not known to have whatsoever parasites or diseases that can be directly transmitted to humans. Hunters are reminded that proper treatment and grooming of wild game meat helps ensure food safety and quality.

Wolves

Wolves and coyotes and hybrids of these species are found in Ontario. Gray wolves and gray wolf hybrids are institute in both the northwest and northeast areas of Ontario and are the most effective at preying on moose. The number of gray wolves and their hybrids varies beyond the province simply has been relatively stable overall for some time.

Human relationship betwixt moose, deer and wolf populations

Higher populations of prey species, such equally moose and deer, can support higher populations of wolves. Predation rates on moose by wolves tend to increment in tandem with moose numbers. This naturally regulates the density of the moose population and is ultimately beneficial to moose and the ecosystems they rely on.

At very high densities, moose populations can degrade their own habitat, and feel increased occurrences of parasites such every bit winter ticks. Moose with brain worm or loftier numbers of winter ticks may exist easier wolf casualty in late winter.

Differences in wolf predation across Ontario

The ministry building studied moose predation in northwest and fundamental Ontario by placing radio and GPS collars on moose. The results show broad variation in the rate of wolf predation by area and wolf pack size.

Wolves were estimated to have acquired half of the adult moose deaths recorded during the study in Ontario's northwest. In comparison, wolves caused relatively few moose deaths in the Algonquin Provincial Park area in central Ontario. Outside of Algonquin, where wolf populations were lower, hunting and other natural factors caused more moose deaths.

The diet of wolves has also been studied in northwestern and northeastern Ontario by collecting scats (droppings) and analyzing their contents. In northeast Ontario, where moose density and dogie numbers were low, moose was the primary prey of wolves during wintertime, but beaver was the well-nigh common casualty consumed during the remainder of the yr. In contrast, studies in northwestern Ontario and southwestern Quebec take shown moose remain an important food item for wolves throughout the twelvemonth in those areas.

Wolf predation and wolf pack sizes

Wolf packs in Ontario are usually quite small, although packs as big as xix wolves have been documented. Pack size and the number of packs in an area vary beyond Ontario, depending on the amount of casualty available. Farther due north, where prey abundance is lower, wolf territories don't encompass the entire landscape and some moose are able to live in areas with few or no wolves.

Generally, the number of moose killed by wolves increases with moose density and the number of moose living within wolf territories. Larger wolf packs kill more moose than smaller packs. Merely the increase in moose killed over time is not proportional to the increase in pack size. So, larger wolf packs really kill fewer moose per wolf than smaller packs.

Wolf predation and hunting

Generally, wolves prey more often than not on young moose and older moose past their prime, and consume few prime-breeding-age moose. Nonetheless, moose populations in areas that are the most heavily hunted tend to include fewer calves and older moose. As a issue, wolves casualty on more than prime number-breeding-age moose during the winter months in these areas. This results in overall higher bloodshed of moose and may reduce moose population growth.

Wolf predation and roads

Ontario enquiry has found wolves motion at a higher rate on roads. These higher travel rates, in turn, lead to more encounters with moose. As a result, more moose are killed by wolves in areas that are closer to roads.

Results of wolf removal

The number of moose killed per wolf pack will not significantly decrease equally the pack size is reduced, so removing just a few wolves from each pack will not decrease overall predation on moose. Simply the removal of an entire pack can essentially reduce predation only this practise may not be ecologically or socially desirable. Changing hunting and trapping regulations to let more wolves to be harvested is unlikely to remove an entire pack. Pack removal often requires intensive removal techniques such as aerial gunning or poisoning practical over several years. Simply in limited circumstances may modest reductions in pack size result in small-scale reductions in predation that benefit moose populations in localized areas.

Some provinces and states have undertaken wolf control efforts. After command measures were discontinued, wolf populations in Alaska, British Columbia, Quebec and Yukon soon recovered to pre-control levels. For case, in the Papineau-Labelle Biological reserve in Quebec, wolf numbers recovered to previous levels less than a year after a 71% reduction in wolf numbers. Once wolf populations recover, moose populations typically return to pre-command levels.

The Strategy for Wolf Conservation in Ontario directs wolf management in the province. The goal of wolf management is to ensure ecologically sustainable wolf populations and the ecosystems on which they rely for the continuous ecological, social, cultural and economic do good of the people of Ontario. Achieving this goal requires the consideration of both ecological and social values and interests.

Bears

Black bears, a predator of moose, inhabit most of Ontario'southward forested expanse. Their range covers about 90% of the province, from Lake Ontario due north to parts of the Hudson Bay Lowlands.

In 2010, it was estimated that at that place were 85,000-105,000 bears in the province.

Algonquin-expanse written report

Researchers compared moose calf survival in Algonquin Provincial Park and in nearby Wildlife Management Unit of measurement 49. This research looked at the importance of predation, among other factors, on moose dogie mortality. Comport population densities were similar inside and exterior the park. Simply, because behave hunting is but permitted outside the park, the makeup of the bear population may differ between the two areas. Predation by both bears and wolves was one of the near important causes of decease for moose calves within the park. Outside the park, hunting and other natural causes were much higher dogie mortality factors. The higher numbers of adult male person bears found in the park may account for the college rates of moose calf predation, since male person bears may be more than constructive predators of moose calves than female person bears.

Studies in Quebec and Alaska

Research has been completed on the interaction between moose and bears in several other jurisdictions. These studies provide insights into moose-comport interactions that are relevant to Ontario.

In Quebec, blackness bears were largely opportunistic predators of moose calves, and ofttimes encountered calves incidentally while moving through their preferred habitat. Extensive movements past bears can lead to more encounters with moose calves. Studies from Alaska take shown that black bears may be a pregnant cause of death for moose calves during spring and summer.

Impact on moose

Most studies have shown that some blackness bears casualty on calf moose that are less than two months of historic period. (In contrast, wolves prey on moose throughout the year, mainly targeting young moose and moose that are past their prime number breeding historic period). These studies show that rates of blackness deport predation on moose calves vary a great deal, depending on ecosystem, habitat and landscape conditions. In a robust moose population, even high levels of predation by black touch moose calves may non affect moose population growth. Just a moose population that has been affected past other factors may exist more sensitive to the affect of bear predation on calves.

Results of bear removal

Several studies have looked at the outcome of black comport removal on moose populations. The results of these studies can exist difficult to interpret because of the circuitous ecological relationships in landscapes that take multiple predator and casualty species. It can too be difficult to rule out other factors that may be affecting moose, such as habitat changes.

Deport removal research has generally shown that:

- low density moose populations may benefit in an expanse in the short-term

- moderate or high density moose populations may non do good

- any benefits to moose are curt-lived as bears recover quickly once removal ends (equally bears from surrounding areas motility into the area where removal occurred)

Ontario's approach to managing blackness bear is outlined in the Framework for Enhanced Black Behave Management in Ontario. The goal of black carry direction is to ensure sustainable black bear populations beyond the landscape and the ecosystems on which they rely for the continuous provision of ecological, cultural, and optimal economic and social benefits for the people of Ontario.

Climate change

Climate change could dramatically alter Ontario's ecosystems by irresolute temperature and atmospheric precipitation. Moose may be afflicted by these changes in the following ways.

Heat stress

Moose are adjusted to extreme cold and deep snowfall weather condition. But they get stressed when summer or winter temperatures rise above a sure threshold.

Since 1997, in the boreal forest of northeastern Canada:

- at least 10 winters accept had warmer than normal temperatures

- at least 12 winters have had less than normal precipitation

Decreased reproductive fitness

Moose feeding is reduced in long periods of loftier temperatures. This lowers the fat reserves that moose need for winter. This reduction in fat reserves could result in an inadequate quality or quantity of milk for calves. Calves with too little milk or poor quality milk volition have poor body condition for winter and may have increased hazard of dying.

Warmer and more than variable early fall temperatures could lower calf product by causing:

- a delay in breeding, which could result in college hunter success and overharvest

- a mismatch in the breeding menstruation for bulls and cows, which could reduce the number of cows that are bred

Parasites

Warmer temperatures, peculiarly in mild autumn and early spring weather condition, tin event in increased tick infestation on moose.

Increased numbers of white-tailed deer

White-tailed deer can more hands survive winter when less snow falls. A larger white-tailed deer population could:

- increase the number of wolves, which prey on both deer and moose

- transmit the parasites brain worm and liver fluke to moose at a higher charge per unit

Changes in moose habitat quality

Changes in climate can touch on the quality of moose habitat. This can change the geographic distribution of moose, every bit habitat becomes more or less suitable.

Warmer temperatures and reduced precipitation in summer can also increase the fire hazard. This may significantly increase moose habitat in some areas.

Increased fire frequency is expected to do good moose past creating early successional forest habitat, or new growth, which provides good food for moose. This is ane of the habitats important to moose.

Potential hereafter effects

Ontario has studied how climate change could affect habitat and species in the future. These studies utilize predicted seasonal temperatures and precipitation. They help to forecast the health of species, including moose. These forecasts can assist with moose management planning.

The predictions vary, past the fourth dimension scale and climate change scenario used.

Ane forecast suggests that, by the twelvemonth 2040, moose numbers will begin to decline in southern Ontario, but increase in parts of the northwest and northeast.

What we're doing

Ontario's Cervid Ecological Framework and Moose Direction Policy recognize the need to consider the best bachelor cognition to address challenges such as climate change.

Ongoing enquiry volition:

- improve our understanding of how climate alter will impact moose

- help to identify the key factors influencing the size of Ontario'south moose population

- guide moose management in the province

Ongoing monitoring will:

- rails moose population trends

- support our adaptive and responsive approach to moose management

Source: https://www.ontario.ca/page/factors-affect-moose-survival

0 Response to "what would be an abiotic factor that may be important to the survival of white tail deer"

Post a Comment